About the Brewery

About Yamahai and Kimoto

The history of sake brewing in Japan appears to go back to the Jomon period (the neolithic age), when people would chew grain to allow enzymes in their saliva to create sugars, gather the chewed grain in a pot, and then allow natural yeast to convert the sugars into alcohol for something called kuchikamizake, or “mouth-chewed sake.”

The word sake also appears in Japan’s oldest histories, like the Kojiki or Nihon Shoki, so we know that it has been a part of Japanese culture since ancient times. The basis for modern brewing techniques, though, was developed in the early Edo period with the kimoto process. This is a way of making a stable fermentation starter using natural lactic bacteria, which began in the area around Osaka and eventually spread nationwide. Yamahaimoto, which removed a part of the hard manual labor of the kimoto starter process, was developed in the Meiji period, and was soon followed by sokujomoto–the most common modern “quick fermentation starter” method.

Personally, I find that part of the attraction of the older yamahai and kimoto methods is the work of natural microorganisms, something lacking in the purely chemical sokujomoto quick starter method. The sokujomoto process includes adding lactic acid into the fermentation mash, so that the primary worker in the fermentation starter is yeast alone. On the other hand, when making yamahai or kimoto sake, the process depends heavily on other vital microorganisms, like lactic acid bacteria and nitrate-reducing bacteria, appearing at just the right time to play their part in the starter. Then, if you’ve made strong kōji, the fermentation starter’s sugar levels will rise, and with protection from the acids those bacteria produced, the yeast will be free to grow and multiply without danger of contamination from harmful bacteria. Sake made with yamahai and kimoto fermentation starters will express truly sake-like umami and clarity of flavor, and will be perfect for aging for even greater depth of flavor. These two starter methods are ideally suited for the kind of sake we hope to make.

[reference]

Yamahai: A traditional sake starter (made without grinding process)

Kimoto: A traditional starter culture (without (natural) lactic acid fermentation). The process of kimoto making has a step of motosuri, grinding of rice and koji.

Kurabito (Brewery Workers) and What They Do

For most of the long history of sake brewing in Japan, kurabito would live at the brewery during their work. We still follow this old-fashioned style of staying at the brewery during brewing season. For about five or six months of the year, we sleep and eat all three meals at the brewery. We might even spend more time with each other than with our families!

When making sake, it’s important to be able to check things immediately when concerns arise. In the quiet of the evening, checking up on the kōji or fermentation starter, and even listening to the fermenting mash, can offer invaluable information. We use our five senses to the maximum, and at times it feels like we even need a sixth. We must gather accurate information from the microorganisms, and must be able to react quickly when necessary. That requires us to stay next to the brewery, and in fact doesn’t put that much stress on the body. And since all the workers take meals together, it allows us to get to know each other better. We get to know each other’s likes and dislikes, and how we think. You can’t make sake without teamwork. Building bonds like this allows us to work together and achieve our shared goal of brewing the best sake we can.

The Brewing Process

Washing & Soaking

This is the first vital step. In particular, carefully soaking the rice after washing helps determine the amount of water it absorbs, which in turn can control the success of kōji-making, and the rate of dissolution in the mash. The rate of absorption depends on the condition of the year’s rice harvest, the rice’s beginning moisture content, and the milling ratio. Hitting the target moisture content is a fundamental element in creating the eventual flavor of the sake.

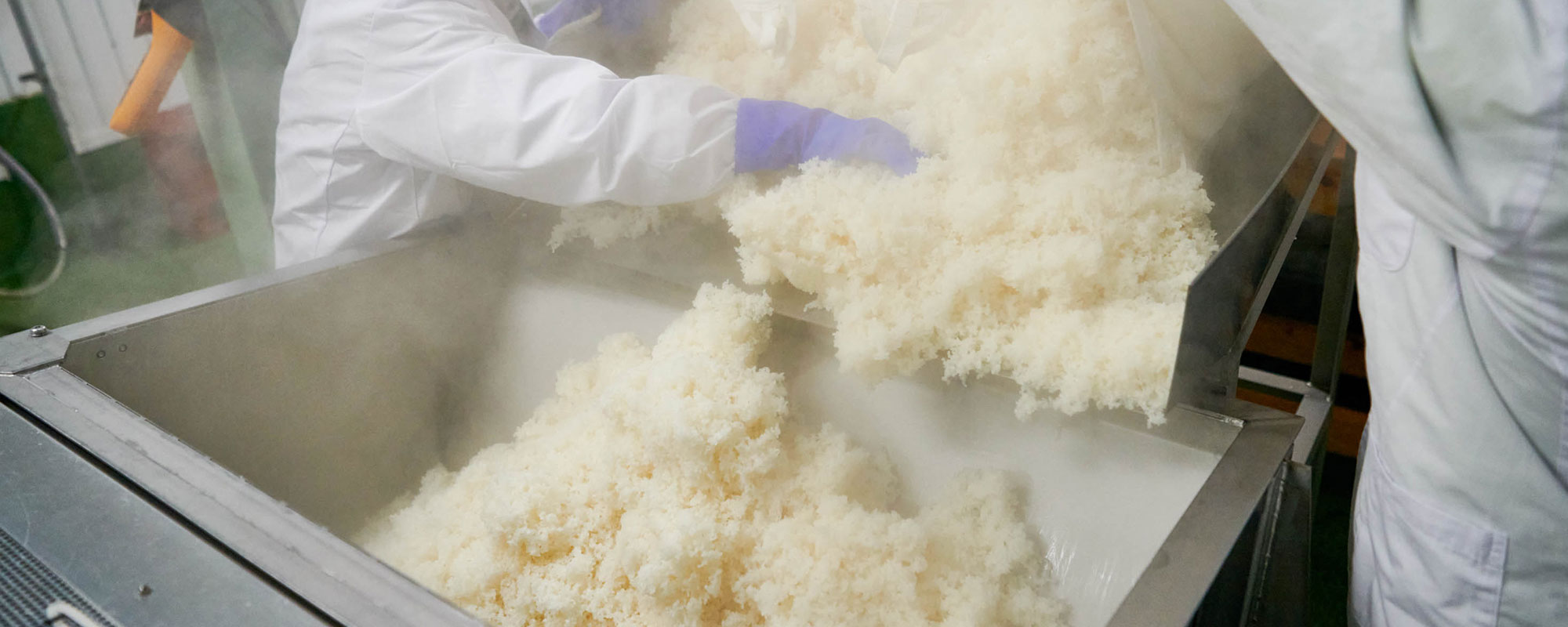

Steaming

Rice cooked for the table is usually boiled, but for sake brewing it is steamed. It is important to obtain rice that is soft on the inside, while firm on the outside. Properly steamed rice allows better working of the kōji enzymes, which can dictate the final elements of the sake’s aroma and flavor.

Kōji

Making proper kōji is the most difficult, and most important, step in the process. It is no exaggeration that kōji making can determine over 90% of the sake’s flavor. Not only does it control flavor, but kōji is also vital in producing good aromatics.

When talking about kōji, my teacher, Noguchi Tōji, taught me “Let it grow, let it dry, let it age,” or in other words, let the kōji penetrate deep into the rice’s heart, then carefully control the moisture evaporation. Then, you must wait for the flavor of the kōji rice to change from sweetness to umami.

Making kōji is an essential part of brewing the kind of sake we want: one with clear umami and a clean finish.

Shubo

The key to making fermentation starter is to create an environment with lots of healthy, active yeast cells.

Raising strong yeast requires a nutrient-rich environment, but to continue and thrive, it must be a somewhat harsh one. Yamahai and kimoto fermentation starter are particularly harsh, as the high acidity, sugar content, and alcohol inhibit the growth of microorganisms. Yeast has to be strong to grow in such an environment.

Strong yeast can maintain its balance even in the latter half of the main fermentation, which is key in making a clean finishing sake.

The Main Mash

Once we mix the best kōji, healthy fermentation starter, mashing rice, and water, it is time to leave the work to them and simply help protect a well-balanced main mash. Once those elements are put together for fermentation, there is no turning back. We visually check the state of the mash every day, and control the fermentation temperature. Then, we must wait for the perfect time to press.

Pressing

Pressing is not the goal, but a turning point. Measured data points can guide us in the timing, but the true deciding factor is taste. How much sweetness is left when we taste it? When that sweetness fades and becomes umami, then we know it is time to press. And when will that sake be distributed? How long do we think it should be matured? We must look into a fairly distant future when we press. We can’t rush this step, and if we have any reservations at all, we wait a day.

Maturation

Matured sake is a gift of the gods. After bottling, we store the sake in refrigerators or underground, and wait for the flavors to come into alignment. Maturation brings delicacy and smooth depth that fresh sake simply does not have. We age our sake for a minimum of one to three years, and determine the length of aging based on the type or condition of each sake. Bottle aging offers a more stable maturation than tank aging. The sake we make with this process isn’t showy, but understated, and matches well with any meal.